Don’t want to read the article?

Listen to the podcast instead.

Everyone has said it.

Everyone has heard it.

But few people pause to consider the consequences when they say it.

“Can you just…”

It’s almost taboo to say “scope creep” in front of a client.

And the irony is the moment we stop talking about it, we start paying for it.

This is an attempt to sit in that discomfort. To explore why scope creep happens, how it is perceived by clients and suppliers alike, and what we can learn by examining it calmly and honestly.

The client perspective

Why “can you just” feels reasonable

From the client’s point of view, “can you just” often feels entirely reasonable.

Most projects do not begin with perfect clarity. Requirements evolve as ideas are tested, stakeholders engage, and work is seen in context rather than in theory. What appeared complete on paper can feel different once it takes shape.

In that environment, small adjustments feel not only acceptable, but necessary.

A line of copy that does not quite land.

A visual that works technically but misses the tone.

A report that answers the question asked, but not the question that now matters most.

From the client’s seat, these moments are rarely seen as changes in scope. They are seen as refinements. Improvements. Sensible course corrections in pursuit of a better outcome.

Small requests deserve the same clarity as large ones.

Clients are also operating within their own pressures. Internal priorities shift. Deadlines move. New stakeholders appear late in the process. Senior decision-makers may see the work for the first time and bring fresh perspectives. In many organisations, the person commissioning the work is not the final approver.

When those dynamics change, asking for “just one more thing” can feel like the most efficient way forward.

The issue is not what is asked, but what unseen impact is set in motion.

There is often an assumption, unspoken but widely held, that small requests are absorbed easily. If the request feels minor, the effort behind it must be minor too. In knowledge-based and creative work especially, much of the labour sits below the surface. Progress is not always visible from the outside.

What feels obvious to one side is often invisible to the other.

In many cases, it is thoughtful. Clients are trying to get the best possible outcome from what they’ve already invested.

Clarity early is cheaper than correction later.

It is not a demand. It is a question.

And questions, when left unexamined, have a way of becoming expectations.

This creates an opportunity for clients. Not to stop asking, but to ask better. The way a request is framed can shape the conversation that follows. A small pause to understand impact, effort, and trade-offs can prevent misunderstanding before it takes hold.

The question is not whether change is allowed. It is whether it is understood.

The supplier perspective

Why the answer is often “yes”

From the supplier’s side of the table, “can you just” often lands very differently.

What sounds like a small request can arrive at a moment when time, budget, or energy is already stretched. The work may be technically complete, but not commercially complete. The effort invested so far is real, even if it is no longer visible.

And yet, the instinctive response is often to agree.

Saying yes feels collaborative. Professional. Reasonable.

For many suppliers, particularly in competitive markets, there is an unspoken pressure attached to saying no. Fear of appearing difficult. Fear of damaging the relationship. Fear of losing future work. In that context, accommodation can feel like the safest option.

Saying yes without context is still a decision.

There is also a genuine desire to do good work. Most suppliers care deeply about what they deliver. If something is not quite right, the impulse to fix it is strong. Drawing a clear line between professional responsibility and commercial boundaries is rarely straightforward, especially when relationships are valued and long-term.

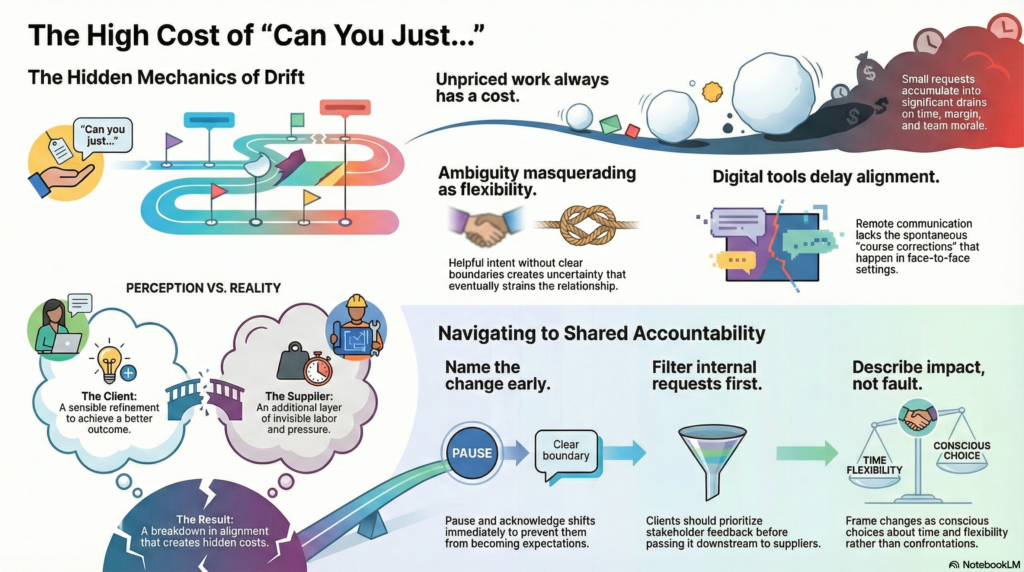

Over time, small requests begin to accumulate. Each one carries a cost, even when it appears minor. Extra hours. Reworked thinking. Extended timelines. Opportunity cost as other work is delayed or compressed. Individually, these costs feel manageable. Collectively, they compound.

Unpriced work still has a cost.

Usually in time, margin, or morale.

Suppliers often struggle to articulate this impact in the moment. The full cost of a change is not always visible until after the work has been done. By then, the opportunity to reset expectations has passed, and raising the issue can feel uncomfortable or transactional.

This is often where boundaries begin to blur.

Ambiguity masquerading as flexibility

Let’s explore this. It’s very relevant and key to us understanding the balance between being accommodating to the client and being commercially savvy.

Flexibility is an important part of healthy client–supplier relationships. Being responsive to change, open to discussion, and willing to adapt are all signs of professionalism.

But flexibility only works when it is built on clarity.

Problems arise when the desire to be helpful replaces the need to be clear. When scope is left loosely defined in the name of momentum, flexibility can quietly turn into uncertainty. What was once a conscious decision to accommodate becomes an assumption that boundaries no longer exist.

In these moments, no one is deliberately avoiding responsibility. Both sides are often trying to preserve goodwill and keep progress moving. The supplier may hesitate to slow things down by raising questions. The client may assume flexibility is simply part of the service. Without explicit conversation, assumptions replace agreement.

Saying “yes” to out-of-scope requests simply shifts the cost elsewhere.

Over time, this pattern creates frustration on both sides. The supplier feels stretched and undervalued. The client remains unaware that anything has changed at all. What began as goodwill gradually becomes a strain.

None of this is about bad intent. Suppliers say yes because they want the work to succeed. Because they want the client to be satisfied. Because they believe flexibility is part of being professional.

But professionalism also includes clarity. And clarity, when delayed, becomes harder to introduce later.

Revisiting the scope is not a failure of delivery. It is an essential responsibility of leadership.

Subjectivity, creativity, and disagreement

When the work is right, but the answer is no

This is often where things start to feel uncomfortable.

In creative, advisory, and knowledge-based work, outcomes are rarely objective. Two people can look at the same piece of work and walk away with very different reactions. One feels the work has landed. The other feels it has missed something important.

A design does what it was asked to do, but not how it was imagined.

An edit is technically strong, but does not feel right.

A strategy answers the question that was originally posed, but not the one now being asked.

From the supplier’s point of view, the work may be sound. From the client’s point of view, it may still fall short.

Creativity is in the eye of the beholder.

This is not a flaw in the process. It is simply the nature of subjective work. Taste, judgement, and context all shape how outcomes are assessed. The challenge is not that views differ, but what happens when they do.

This is often where scope quietly re-enters the conversation.

When a client asks to go back to the drawing board after days of work, the request can feel entirely reasonable to them. They are responding to what they see. They are trying to get to the right outcome. From their perspective, the work just is not there yet.

For the supplier, that same request can mean starting again. Reworking thinking. Re-editing, redesigning, or reframing something that was already delivered in good faith.

This is not always scope creep. But it is always consequential.

Not all extra work is scope creep. But all unclear expectations eventually become someone’s problem.

Much of the tension here sits around approval.

Approval is often given before alignment is actually reached. A nod in a meeting. A short email. A sense that it is good enough to keep moving.

Approval is sometimes permission to move on, not confirmation that the work is right. That distinction is rarely discussed at the time, but it matters later.

Preliminary reviews can help, but they are not a cure-all. Early feedback reduces risk, but it does not remove differences of opinion. What it does do is surface them sooner, while there is still time to respond without starting again.

If taste is still evolving, the work is still evolving.

The lesson here is not that disagreement should be avoided. It is that it should be addressed.

When differences of opinion are addressed early, they can be managed. When they are left unspoken, they quietly reshape scope without ever being discussed.

The takeaway is simple. In work where judgement and opinion matter, alignment is not a moment at the end. It is an ongoing conversation that needs to be explicit on both sides.

When communication changes, alignment does too

Much of what has been discussed so far is not new. What has changed is the environment in which these conversations now take place.

The spoken word has increasingly been replaced by the digital one. Emails, messages, comments, and shared documents now carry conversations that once happened informally, in passing, or in real time. While these tools bring flexibility and reach, they also change how meaning is conveyed.

Written communication leaves less room for casual clarification. Tone is easier to misinterpret. Intent can be lost. A message written quickly can be read slowly, carefully, and sometimes defensively. What was meant to be provisional can feel final once it is captured in writing.

There is less space for spontaneous alignment.

The quiet “oh, that’s not what I meant” moment is harder to come by. Those small course corrections, which once happened naturally through conversation, now require follow-up messages, scheduled calls, or larger meetings to resolve.

Remote and hybrid working has amplified this shift. Digital meetings have replaced many face-to-face interactions, but those meetings are often planned rather than spontaneous. They tend to involve more people, more structure, and more formality. As a result, language becomes more formal than intended, and discussion is delayed until everyone can be present.

Decisions are delayed not only because people are cautious, but because attention is diluted. In larger, more formal settings, not everyone is equally engaged. Some feel the discussion does not require them. Others are present but distracted, half-listening while managing competing priorities.

This is not a criticism. It is simply how modern working plays out.

When alignment relies on crowded calendars and fragmented attention, clarity becomes harder to achieve. Important nuances are missed. Hesitations go unspoken. Assumptions are carried forward because there is no natural moment to challenge them.

The risk is not that people stop communicating. It is that communication continues without shared understanding. Messages are exchanged, but alignment is deferred.

As communication methods evolve, the way alignment is created and maintained has to evolve with them.

In this environment, leadership shows up in how quickly uncertainty is addressed, not how long it is allowed to linger.

Not every discussion needs an audience. Not every decision needs to wait.

Where things actually break down

If everyone has good intent, why does this keep happening?

By now, it should be clear that scope creep rarely starts with bad behaviour. Clients want better outcomes, suppliers want to be helpful, and most people involved believe they are acting reasonably. And yet, the same patterns repeat.

Where things actually break down is not in the work itself, but in how the work is held together.

Many projects rely on goodwill to bridge the gaps. Experience, flexibility, and the assumption that things will balance out over time often carry the work forward. For a while, that approach works. Then pressure increases, expectations shift, or new voices enter the conversation, and the gaps start to matter.

This is when scope begins to drift.

Rarely all at once. More often through small changes that feel insignificant in isolation. One extra request. One quiet adjustment. One more “can you just.” No single moment feels important enough to stop the work and reset the conversation.

Eventually, someone realises the work no longer looks like what was originally agreed. By then, raising it feels awkward. Time has been spent, momentum has built, and the work is already moving.

This is usually the point where questions about responsibility surface. Should this have been anticipated? Should there have been an allowance for change? Who, exactly, was expected to notice when the work moved off course?

In practice, both sides often assume the other is managing this. The client may assume flexibility is built in, while the supplier assumes there will be a moment later to reset expectations. Neither assumption is always stated, and that silence allows drift to continue unchecked.

In many types of work, particularly creative, advisory, and complex delivery, change is not unusual. It is normal. Treating it as an exception does not prevent it. It simply delays the conversation about how it should be handled.

That delay is what creates discomfort later. Not because the work has changed, but because no one stepped in early enough to manage how it was changing.

This is where leadership matters on both sides.

Clients have a responsibility to manage their own house, to filter requests, align stakeholders, and decide what genuinely needs to change before asking suppliers to act. Uncontrolled input almost always leads to uncontrolled scope.

Suppliers, in turn, have a responsibility to speak up sooner. To flag when work is drifting, and to make the trajectory of time, cost, and effort visible before it becomes a problem. Silence, even when well intentioned, allows misunderstanding to grow.

When neither side takes this role seriously, scope does not get actively managed. It is simply tolerated until the cost of that tolerance becomes impossible to ignore.

The real lesson here is not about blame. It is about shared accountability.

Change should not come as a surprise. Not because it will not happen, but because both sides should expect it, notice it, and manage it together.

Good intent helps. Clear leadership, on both sides, does more.

Mitigation without confrontation

How to make scope a normal conversation

By this point, it should be clear that scope creep is not something to eliminate. It is something to manage.

The difficulty is rarely recognising that change has occurred. It is knowing how to raise it without creating friction, defensiveness, or embarrassment on either side.

This is where tone, timing, and language matter.

A familiar scenario. A project is moving well. A request comes in that feels small, but different. No one uses the phrase “scope creep”. The work continues. A few days later, the shape of the project has clearly shifted.

The opportunity to respond sits in that first moment.

Absorbing the change quietly avoids discomfort in the short term. Reacting defensively creates it immediately. Neither tends to lead to good outcomes.

A better response is to pause and acknowledge the shift without judgement.

“This feels slightly different to what we originally discussed. Can we take a moment to look at the impact before we move forward?”

It doesn’t accuse. It doesn’t refuse. It simply creates space.

Later in a project, the challenge often looks different. Momentum is high. Pressure is real. Feedback reframes the brief rather than refining it. The instinct is to keep going and deal with the consequences later.

This is where making the trajectory visible matters.

“If we head in this direction, it will add time here and reduce flexibility there. We can do it, but it’s worth choosing it consciously.”

Again, this is not confrontation. It is clarity.

From the client side, mitigation often happens internally. Requests arrive from multiple stakeholders. Each one feels reasonable on its own. Taken together, they are not.

Leadership here is not about relaying every request downstream.

It is about filtering and prioritising before action is taken.

“We’ve had a few additional requests come in. Before we pass them on, let’s agree which ones genuinely change the outcome.”

Across all of these situations, the principles are the same.

Name the change early.

Describe impact, not fault.

Offer options, not ultimatums.

Keep the conversation factual and calm.

The earlier scope is discussed, the less emotional it becomes. Raised early, it feels like good management. Raised late, it feels like conflict.

Handled this way, scope stops being a taboo subject. It becomes part of how well-run work progresses.

Closing thoughts

Making the conversation normal

Scope creep is not a failure of planning. It is a feature of complex, human work.

Ideas evolve. Context shifts. People see things differently once work takes shape. None of that is a problem on its own. The problem arises when change is left unspoken, unmanaged, or quietly absorbed.

What makes scope creep uncomfortable is not the change itself. It is the silence around it.

Clients often hesitate to raise scope because they do not want to appear demanding.

Suppliers hesitate because they do not want to appear difficult. Both sides are trying to protect the relationship. Ironically, that instinct can put the relationship under strain.

The most productive environments are not the ones where scope never changes. They are the ones where change is expected, discussed early, and handled calmly.

When scope becomes a normal conversation, it stops being a loaded one.

This requires leadership on both sides. Clients who are willing to filter requests, align stakeholders, and make clear choices. Suppliers who are willing to raise issues early, show impact transparently, and guide the conversation rather than avoid it.

This does not need to be confrontational or stressful. It does not require rigid contracts or constant renegotiation. What it does require is shared understanding, clear communication, and the confidence to talk about change before it becomes a problem.

Scope creep is not usually malicious. It is usually human, and human problems are best solved through clear, timely conversations.

The teams that handle scope well are not the ones that try to avoid change. They are the ones that notice it early, talk about it openly, and decide together how to move forward.

That is not just good delivery.

It is good leadership.